Note: this chapter appeared at the end of Part 2, right after the chapter called “High Concentration.” My editor thought it was too much of a diversion from the book’s main plot – that is, the race to build and steal the bomb. In hindsight, I’ve come to agree with her. See what you think…

The Getaway

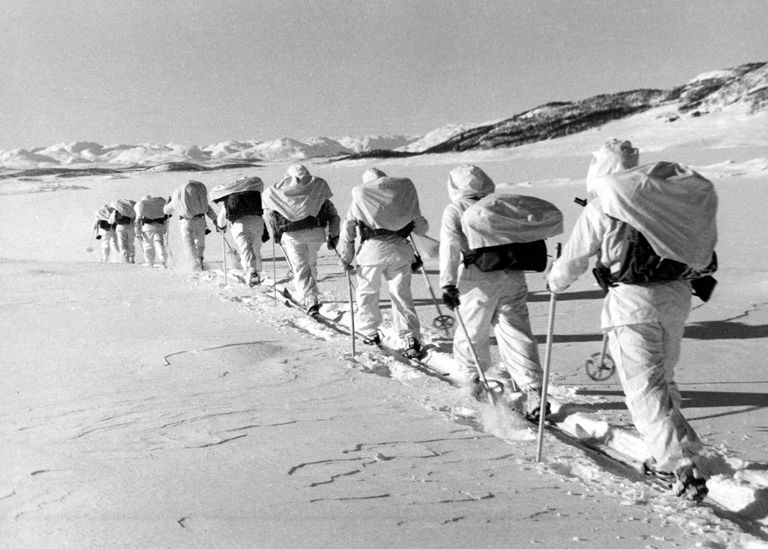

The men split up, most heading on skis to the Swedish border, 250 miles away. Knut Haukelid and Arne Kjelstrup stayed behind in Norway to help organize anti-German resistance. They skied to a mountain hut, found radio equipment that had been stashed by other Norway resistance fighters, and wrote out a short, coded message for London:

“High concentration installation at Vemork completely destroyed on night of 27-28—Gunnerside has gone to Sweden”

Then they prepared to head deeper into the wilderness. “You can bet the Germans are in a fury,” Haukelid said. “And you can be sure that they’ll search every corner of the mountains.”

Only later did Haukelid learn how right he was. Enraged German commanders were already sending out a 10,000-man German force to track down the saboteurs. But most of the men were already well on their way to Sweden, and Haukelid and Kjelstrup felt confident they could hide in the remote mountains forever. The one in real danger was Claus Helberg, whose orders were to return to the Rjukan area to organize resistance fighters.

“I had heard nothing of the German raid,” Helberg later said. “Everything looked normal as I set out across the plateau on skis.”

He skied thirty miles to a cabin the team had used on its way to Vemork. Needing a rest and some warm food, he stepped inside. Instantly he saw the place had been ransacked—chairs lay on their sides, stuffing puffed from ripped mattresses, and the contents of drawers and cabinets were scattered all over the floor.

Helberg dashed out the door, and slid to a stop. Five German soldiers were skiing toward the cabin. They had obviously seen him go in. They were half a mile away and coming on fast.

Helberg had just one weapon, a small pistol. He could not stand and fight. His life would depend on the only other tool he had: his skis.

“In a matter of seconds I had them on and pushed off,” he’d recall.

The Germans opened fire.

“This is the end for me,” thought Helberg.

But then the shooting stopped. Helberg glanced behind him. Realizing they were too far from their target, the Germans had put away their guns, deciding instead to chase their victim down.

“Here we are in the mountains of Norway, where competitive skiing was born,” Helberg remembered thinking. “And now the competition was for my own life.”

Helberg raced across the snow, glancing behind him every few minutes. Three of the soldiers, inexperienced skiers, were losing ground. The other two stuck within about 50 yards. After ten more miles up and down the icy hills, the fourth German soldier dropped out of the race.

“So now there was just the one chasing me,” recalled Helberg. “A good skier, too.”

His muscles on fire, Helberg pushed on another hour. Then another. His pursuer never fell far behind. But Helberg realized something: the German is faster on the downhills, but I’m the stronger climber.

“I therefore tried to find as many hills to climb as I could,” said Helberg, “until finally I went as high as I could and there were no more hills to climb, only hills to descend.”

He started down the slope, pushing forward with his poles. But Helberg could hear the sliding sound of the German’s skis growing closer and closer.

“Hands up!” shouted the soldier in German.

Helberg skidded to a stop, pulled out his pistol, and turned. The German already had his pistol out, pointed at Helberg. They were barely 100 feet apart.

Helberg fired and missed.

The German fired and missed.

Then a thought flashed through Helberg’s mind: they were both exhausted, their muscles shaking. The setting sun was right in the German’s eyes. He was unlikely to hit his target at this range. The best play was to wait for the enemy to empty his six-shot Luger. Either way, it would be over quickly. “I would be either dead or alive—or wounded, in which case I would immediately bring on death by swallowing my suicide capsule.”

The German soldier fired again. The bullet whizzed past Helberg’s ear. The next shot just missed his shoulder. The German aimed and fired three more times, all misses. The whole thing took maybe a second, but to Helberg it seemed to be lasting forever.

Empty pistol in hand, the German suddenly became the prey. He turned and started uphill. Helberg chased. “Every second counted,” he knew. “His comrades might turn up over one of the hills at any moment.”

Helberg, the better climber, closed quickly. He could see panic in the man’s suddenly sloppy skiing.

At 30 yards, Helberg stopped, steadied, and fired at the German. “He began to stagger and finally stopped, hanging over his skis, like a man on crutches,” Helberg said.

“I turned around and pushed on to get away before the others came.”

Helberg saw a lake in the distance. He headed toward it, knowing his skis wouldn’t leave tracks on the frozen surface. He was just beginning to feel safe when he skied off the side of a cliff.

“It was quite an air journey,” he said of the 120 foot drop. “But it was not until I stopped sliding and rolling and came to a stop in a snowdrift that I thought I might be hurt.”

When he tried to push himself up, a bolt of pain shot through his right arm—broken, he knew instantly. Grateful his legs still worked, he got back onto his skis and continued with one pole.

The next morning Helberg came to a small town. Crouched behind bushes, he looked out at the main road. The area was swarming with German soldiers banging on doors, desperate to pick up the trace of the Vemork saboteurs. “I couldn’t have picked a worse place of refuge,” he said.

But he’d been on his skis for 36 hours, and covered 112 miles. His arm was bent unnaturally, and throbbing. He needed food, sleep, and a doctor. Skiing farther was not an option.

Stepping out from the bushes, Helberg walked right up to a German soldier and introduced himself as a local fellow, pro-German, who’d volunteered to help track down the saboteurs. He’d fallen in the mountains and broken his arm. He showed the soldier a fake ID made for him in London—and waited a scary minute while the soldier inspected it. “What they would have done if they had known I was one of the saboteurs they were looking for, I still shudder to think about.”

The German soldier handed back the ID and led Helberg to a doctor. The doctor set Helberg’s arm and wished him good day.

Feeling lucky, and beyond hungry, Helberg broke a basic rule of underground work—he exposed himself unnecessary by walking into a hotel. He got a good meal, but then German soldiers rounded up all 18 Norwegian guests and announced they were being taken to a prison camp for interrogation

“I was very much in doubt as to my next move,” said Helberg. He could not allow himself to be questioned—probably tortured.

Outside the hotel, soldiers began shoving the prisoners down the steps toward a waiting bus. Helberg hung back, hoping to be the last one on, figuring if he got a seat near the door, there might be some way to escape. Seeing Helberg delaying, a soldier kicked him full force in the back, sending him tumbling down the steps.

As Helberg reached out to break the fall with his good arm, his pistol—a gun that could easily be traced back to the German he’d shot in the mountains—flew out of his jacket, spun along the sidewalk, and bumped to a stop against the shiny black boots of a German soldier.

Helberg lay face down on the pavement, thinking: this can’t really be happening.

The German bent down and picked up the pistol. He and another soldier began arguing about what to do. Finally they decided they’d better just follow their orders, which were to get the prisoners onto the bus. They put Helberg way in the back. Four armed guards in motorcycles escorted the bus toward the concentration camp.

Helberg began chatting with a young woman next to him. He made a point of talking loudly and laughing.

A soldier walked back and said, “What are you two doing?”

“Doing?” asked the woman. “What do you mean?

“Stop the nonsense, that’s all,” ordered the soldier.

Helberg and the woman immediately began joking again, making fun of the German guards. The man stormed back.

“Go up to the front of the bus!” he shouted to Helberg. Sitting down next to the woman, the guard said, “From now on, I will sit here.”

Helberg nodded to the woman, seeing in her eyes that she understood he needed to escape. “Luckily,” he’d later say, “I was now in the seat nearest the door, and the Norwegian driver paid no attention to me.”

Just after sunset, the bus slowed at the top of a hill. Helberg leaped up, pulled the door lever, and tumbled onto the road. He could hear the Germans shouting and cursing as he sprinted across a field. He reached the woods just as the bullets and grenades started flying.

He ran until he could no longer run, then walked until he could not take another step. There was a dark farmhouse. He tapped on the window. The farmer called a doctor, who took Helberg by ambulance to a hospital, locked him in a room, and told everyone that behind the padded door was a “dangerous lunatic.”

German soldiers came to search the hospital but left the lunatic alone.

Three weeks later Helberg borrowed skis and set out for Sweden.